Introduction to Desert Racing

HOW IT WAS IN 1951

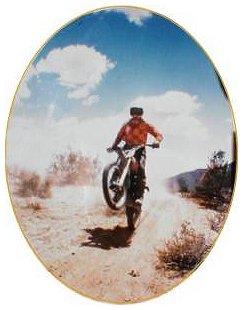

A desert racer rides flat out for a hundred miles or more over some of the most hostile terrain on earth. Just finishing a desert race requires experience, skill, machine preparation, courage and fierce determination. Every desert racer is a good mechanic or has one working for him. The best motorycle in the world will not last a season of desert racing without regular and knowledgeable maintainence. In desert racing, almost everyone is smiling when they roll into the finish line and collect their finisher's pin.

A desert race begins with more than 500 "bikes" on the starting line: engines dead, levers poised, eyes focused on a banner fluttering in the breeze. When the sponsoring club drops their colorful banner, the silence is broken by the roar of two-stroke engines coming to life and hundreds of riders racing into the desert to challenge the rocks, the cactus and each other.

A typical race in the desert consists of two 40-mile loops. When the course consists of two separate loops, the race is called a Hare & Hound. When the course consists of one loop ridden twice, the race is called a Hare Scrambles. In the hot, Summer months, riders compete on 6-8 mile courses called European Scrambles. Courses are marked with lime tossed on the ground, surveyor's ribbon (usually hot pink), directional arrows (left, right, down, up) and 7X9 day-glo orange cards. The District has strict rules to keep riders on course and as safe as possible. Mouse over any icon for more information about that course feature.

The first few miles are unmarked, giving riders time to fight for position. After the smokebomb, the course narrows significantly, so the "bomb" is the target of every rider when the banner comes down on a desert race. Years ago, burning tires identified the beginning of the marked course. Now, for environmental reasons, the "bomb" is simply an array of surveyor's ribbon wide enough and tall enough to be seen from the starting line several miles away. The simultaneous convergence of several hundred riders at the bomb can quicken the heartbeat of even the most hardened racer.

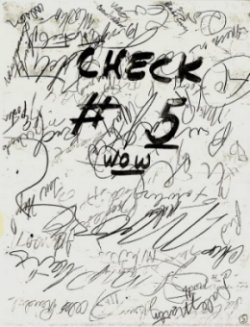

Smart clubs place checkpoints at strategic locations where cutting the course means missing a check and being disqualified. Some are "flying" checks, where you keep on going, but most checkpoints require you to stop to get your checkpoint card marked as proof that you rode the entire course --, your "ticket" to a finisher's pin! In the old days, you duct-taped your card to the gas tank, then stopped at each check to have one of the check personnel sign your card with their name. Later, the check personnel used a colored crayon for each checkpoint. If you got gas on the card, it usually made the crayons melt into one big, colorful glob! Sometime in the 80s, the card was moved to the front fender. Riders roaring into a check and roaring out again make checkpoints an exciting place to witness the drama of desert racing. Check it out!

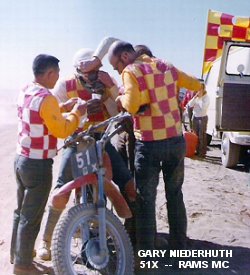

Another exciting place to see and hear the action is in the gas pits. Each desert club provides a pit crew for its riders. After 40 or so miles of racing through the pucker bushes, you've gotta find your club banner among all the dozens of others. Explosions of dust and dirt rise into the air as riders pull in and out of their pit areas. Banners of every color and pattern wave in the hazy sky. Spectators run here and there screaming and waving at their favorite racers. And pit crews work frantically to give their guys (and gals) that racer's edge. In the old days, the race didn't stop in the pits -- today there is a 15mph speed limit.

Clubs are the life blood of desert racing. They organize and conduct all desert events, support riders during a race, provide a social atmosphere for riders and their families, and battle big government (BLM) to keep the desert open and desert racing alive. The club-oriented nature of desert racing makes competition keen, exposes the beginner to valuable experience and builds a comradship unequaled by motorcycle competitors anywhere. Sharing a common enthusiasm for motorcycles in general, and desert racing in particular, builds understanding, respect and friendship. If you break down during a desert race, your buddies will come and get you. But you better have one helluva good reason for not fixing the problem yourself, and riding it in!

| MINI | LW - II | LW - I | HVY WT | |

| K I D S |

|

|||

| M E N |

|

|

|

|

| V E T E R A N S |

|

|

||

| S E N I O R S |

|

|

||

| M A G N U M S |

|

|

||

| Women & Super Seniors can race any size bike they choose | ||||

Every desert race is actually more than 40 races taking place at the same time on the same course -- four skill classes, four engine-size divisions and six age groups:

- Four Skill Classes...

- Beginner - white plate

- Novice - green plate

- Amateur(Intermediate) - yellow plate

- Expert - red plate

- Four Engine Sizes... (plus Quads)

- Mini (0-85cc)

- Lightweight II (0-200cc)

- Lightweight I (201-250cc)

- Heavyweight (Over 250cc)

- Six Age Groups...

- Youngsters (12-15)

- Open (14-whatever!)

- Veterans (30+)

- Seniors (40+)

- Masters (50+)

- Super Seniors (60+)

Every desert racer has a number plate on his bike with a colored strip to identify his or her skill class: white for Beginners, green for Novices, yellow for Amatuers and red for Experts.

Riders can transfer from Beginner through Expert by accumulating points according to their finish position within a class and division. One of the thrills of desert racing is being notified that you have been "transferred" to the next skill class. Points are also used to determine the number on your plate. A rider's 20 best finishes during the year determine what number a rider has during the next year of competition. There are 14 number 1 plates, and there is fierce competition for each...

MEN |

WOMEN |

VET 30+ |

SR 40+ |

MAG 50+ |

SSR 60+ |

4-STRK |

QUAD |

MINI |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Whether the women race or not, they are more than welcome at desert events. Behind every successful desert racer stands a good mechanic, hours of practice and a loyal wife or girlfriend. Her job frequently finances the racing and its expenses. She cooks the meals, helps in the pits and waits anxiously for her man at the finish. Desert racing is a family sport.

Besides a good club and a loyal woman (or man!), the desert racer's most valuable asset is eyesight. Traveling at speeds of 50-70mph, or more, across marked but unknown territory requires the ability to distinguish changes in terrain at great distances. After a few years, an experienced competitor can "read" the desert well enough to negotiate rough terrain at incredible speeds. It also takes a strong grip and strong legs to blast across or jump over rough ground at high speed.

Motocross is a good way to learn the basic skills, but desert racing is in a class by itself. Even with a season of motocross under your belt, it will take a while for you to acquire the skills and stamina necessary to get up and down steep, rocky hills and keep your wheels down and your handlebars up in tight, nasty canyons. And you can't win or place unless you finish, so judgment is vital. The experienced rider learns to go as fast as the terrain allows -- no faster and no slower. You can ride a few degrees over your head some of the time, but they don't give trophies at the bomb!

Motocross is a good way to learn the basic skills, but desert racing is in a class by itself. Even with a season of motocross under your belt, it will take a while for you to acquire the skills and stamina necessary to get up and down steep, rocky hills and keep your wheels down and your handlebars up in tight, nasty canyons. And you can't win or place unless you finish, so judgment is vital. The experienced rider learns to go as fast as the terrain allows -- no faster and no slower. You can ride a few degrees over your head some of the time, but they don't give trophies at the bomb!

Over the years, desert racing has gone through many changes. In the fifties and sixties, pretty much everyone raced four-stroke motorcycles from Britain, such as the 650cc Triumph Tiger, the 650cc BSA Spitfire and AJS's 500cc single. In the late 60's, two-strokes like the 250cc Yamaha DT-1 and the 100cc Sachs began to appear on the starting line. By the early 70's, two-strokes from Yamaha and Husqvarna dominated desert races. In the mid 70's, the Yamaha YZ came out with a monoshock rear suspension, and in-gear starting, making it a favorite for many desert racers. By the early 80s, almost all two-strokes had some form of single-shock design for the rear suspension, and watercooling. Today, the two-stroke is pretty much the exception, not the rule -- most desert racers are riding very light, highly sophisticated, water-cooled four strokes.

In the early 70s, District 37 and other governing bodies within the American Motorcycle Association (AMA) added a requirement for exhaust silencers. In the mid 70s, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) began to "manage" desert racing. Desert racers have accepted and even welcomed some of these changes. But a great deal of the early "mystique" of desert racing has disappeared with the loss of several famous point-to-point races. The Barstow-to-Vegas was perhaps the most popular and well-known of these races. Drawing nearly 3500 entrants and covering over 150 miles of desert, the race was the high point of the racing season.

The Check Chase was less well known by the average motorcycle enthusiast, but highly regarded by desert racers as a racerís race. Attracting over 1000 serious competitors, the Check Chase ran from the Mojave Desert near Lucerne, California to the Colorado River near Parker, Arizona. The course included over 200 miles of rough desert and mountain passes, four gas pits and excitement for everyone. It was a challenging, festive event that no longer exists. Desert racing is an endangered sport.

But for many, desert racing was and always will be a very special home away from home -- a people, a place and a sport where you belonged. Whether sitting around a campfire with your buddies or trying to catch one of them in a sandwash, you were home...